Living as a crossdresser and queer man for years, Adamu, who is a Yan Daudu — a group of recognised femme men in Northern Nigeria — prepares to accept traditional norms and marry a woman.

Editor’s note: This story was published in collaboration with FairPlanet as part of the Dual Life Project, which showcases how LGBTQIA persons in Africa are often compelled by society to lead dual lives.

By Rabi Madaki

After years of openly presenting as a woman, 32-year-old Adamu finds himself at a pivotal moment as he prepares to marry a woman.

“I believe it is the right thing to do as a man,” he says about his forthcoming wedding.

Adamu first started presenting as a woman during his teenage years. His early life as a crossdresser unfolded against the backdrop of Ture, his grandmother’s village in Kano State, where his family relocated to after his father’s death.

Like many communal households, Adamu’s grandmother’s home was crowded with relatives, most of whom were women with children who lacked support from their husbands and fathers. An influence Adamu believes played a huge role in defining his identity.

Initially, Adamu’s interaction with femininity was by quietly watching as the women in his family engaged in traditional feminine activities. But as he matured, his fascination deepened and started to shift from mere observation to finding genuine enjoyment in pursuits like making hair and cooking, frequently spending time with his aunts as they partook in them.

Over time, he learned these skills and began to adopt his aunts’ mannerisms, he says. Even in social circles, Adamu naturally gravitated towards women. Most of his friends were female, and through their companionship and support, Adamu felt comfortable enough to express himself openly for the first time.

“When my friends were invited to weddings, I’d follow them and makeup with them as a woman.” His early experiences led him to his first career as a makeup artist for brides, helping with the aesthetic part of their preparation for the ceremony. “Some women gave me the job of doing makeup on them, dressing them up for occasions like weddings and all that.”

Working at weddings allowed Adamu the freedom to express his femininity. Most times, after completing his duties as a makeup artist, he would adorn himself with jewellery, apply makeup, and enthusiastically join the festivities. Each event he worked at solidified his identity as a ’Yan Daudu’ in the eyes of society.

Yan Daudu, translating to Sons of Daudu in English, refers to feminine men within the Hausa society – an ethnic group in the northern settlement of Nigeria. Originating from a historical queer community that predates Islamic influence in Northern Nigeria, these men dressed and behaved in ways traditionally associated with women.

Some interpretations of Yan Daudu portray them as transgender without formal sex change. While that theory is uncertain to be universal, a fact is their feminine mannerisms and astute sense of women’s style, which, according to Adamu, is believed in Northern Nigeria to surpass even women’s sense of style.

“When women in the north are getting married, they like to invite or hire Yan Daudu to help out with the outfits and make-up for their weddings,” Adamu says. “They feel the men do a better job than women, so we get paid well for jobs like that.”

Beyond exhibiting feminine mannerisms, Yan Daudu are also known for their attraction to men. Even though Adamu knows he’s a Yan Daudu, he didn’t discover he was gay till after his university, years past his first open presentation as a woman.

“I wasn’t a fully-fledged Yan Daudu when I was in university,” he says. “It wasn’t until after I finished that I fully realised I was gay. I was never given the title of Yan Daudu; I gave it to myself because I had realised that that was what I wanted in my life. ”

On discovering his identity, Adamu gained support and acceptance from his family, thanks in part to his upbringing in a household with women who understood his interests. Another small feat that also aided his family’s acceptance of his sexuality was financial security.

“My family does not have a problem with my identity because I make money and support them. None of them calls me names, insults me or calls me Yan Daudu.”

Adamu’s journey as a Yan Daudu truly blossomed after he departed from Kano State. Following his graduation, he sensed Kano lacked opportunities, prompting him to seek greener pastures. His journey took him through brief stays in Kaduna, Maiduguri, and Abuja before he eventually settled in Lagos after a chance encounter with a woman.

“She wasn’t related to me, but we were living together in Abuja before she decided to come to Lagos. She brought me along with her,” he says. “She was a local musician, and that’s how we met and started living together. When we moved to Lagos, we were doing music together until she had to travel. I decided to stay back to look for another business to do. People I knew here then introduced me to the food-selling business.”

In Lagos, Adamu faced problems related to his identity for the first time.

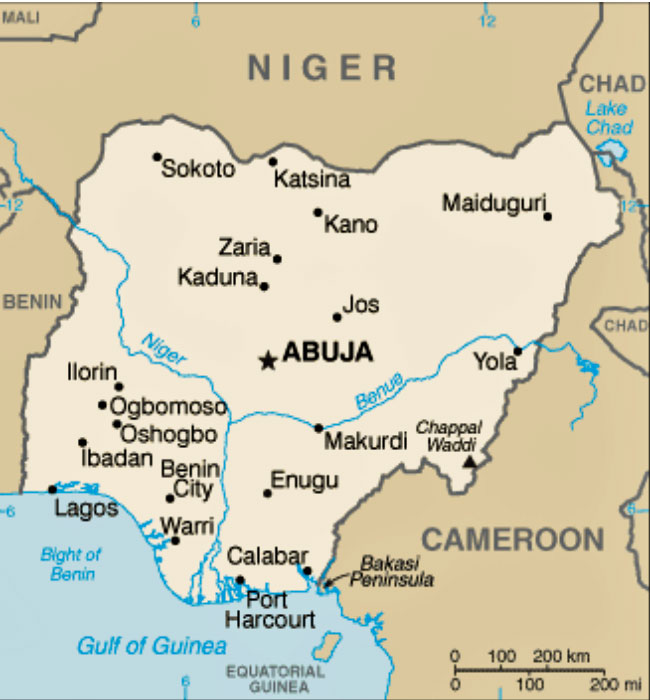

Map shows location of Kano in north central Nigeria and Lagos in the southwest.

“It’s when I came to Lagos that I started having enemies,” he says. “When I was in Kano, Abuja, Kaduna, and Maiduguri, I never had any problems. Here in Lagos, people like looking down on me because of the kind of things (presenting feminine) I do, but I don’t mind them. I’ll keep doing my things and making my money.”

Despite Sharia Law being practised in Northern Nigeria, where men who dress like women can be imprisoned for a year, Adamu adds that being familiar with and having personal relationships with people while growing up influenced how well he was accepted.

“It’s only in Lagos that I keep my way of life a secret to others. People in the North treat me differently because I grew up with them, and I’ve known them all my life,” he says. “I just came to Lagos, and people here don’t know me that well. That’s another reason I have more lovers in the north than here in Lagos.”

Despite the prevalent hostility towards queer individuals in Nigeria, both in actions and words, Adamu’s community treated him with acceptance and normalcy. It was evident from their reaction during weddings, where there was no overt negative response to his expression. Adamu states that based on his experience, the treatment of individuals like him within his community is positive.

“Being gay is not frowned upon in Kano; everyone knows or will eventually know about it, and it’s not a problem.”

This acceptance extends not only to his immediate community but also to northerners he encountered in religious settings.

“Where I pray, people don’t have an issue with me because they know although I’m gay, I am still very religious.”

While the general treatment of Yan Daudu in the north may outwardly appear receptive, a closer look reveals nuances in their societal treatment. In Hausa society, Yan Daudus are treated in a nuanced way that separates sexuality from gender. There’s a prevailing belief that sexuality is viewed more as an act than a defining characteristic of an individual’s identity.

This perspective influences how relationships with men are defined within this cultural context. When Adamu discusses his partners, his tone shows a noticeable distance. He refrains from openly expressing love or discussing whether he misses it, suggesting a complex interplay between societal expectations, personal identity, and t relationships within the Hausa community.

After a decade in Lagos, the acceptance of Adamu’s identity took a strange turn when his mother bought news.

“My mother said I should get married to a woman,” he says. “I am not being forced to marry, and neither am I doing it because of my mother. I believe it is the right thing to do as a man, and Islamically, a man is supposed to get married. My parents are not forcing me; I want to do it to act as a normal man.”

Yan Daudu marrying is indeed a common practice. This occurrence is not isolated but rather emblematic of a troubling marriage culture where Yan Daudus marry women to fulfil societal expectations of masculinity.

For some Yan Daudus, marriage doesn’t alter their identity. Even though they may continue their way of life, their marriage doesn’t change this aspect. Interestingly, the women they marry are often aware of their partner’s lifestyle and choose to proceed with the marriage.

Adamu explains, “The lady I’m going to get married to already knows about my way of life, so it’s not a secret.”

This story is published on Minority Africa and appears with permission in this publication.

COMMENTS